Is Isolation a boon for creativity and a bane for sanity?

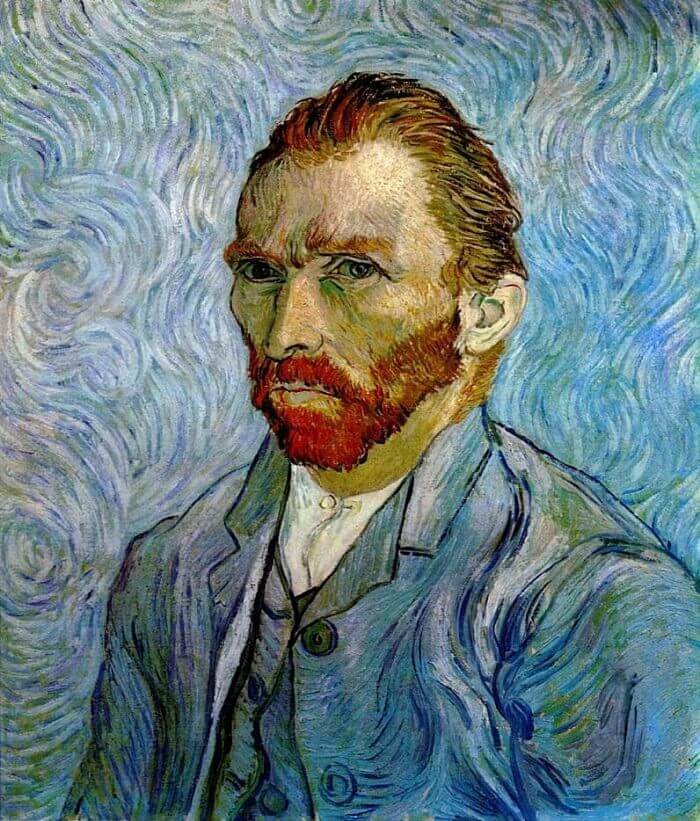

“Isolation”, in its various forms and corollaries, has almost turned into a topic discussed as frequently as the weather to a Londoner. While some writhe with the grief of isolation, some rejoice the bliss. On one of my rainy self-isolation days, as I sit on outhouse rocker with a brewing cuppa, I could not help but spare a thought of Van Gogh. How did he rejoice or regret is isolation days?

At age 36, around May 1889, he decided to move to Auvers-sur-Oise, a sleepy town in northwestern France where he lived for 53 weeks in the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole. The asylum had only 18 male residents with little interest in art, who Van Gogh called as “companions of misfortune”. The environment represented a stark contrast from the glitzy art capital of Paris and the avant-garde of the art fraternity that he had left behind. But isolation also brought its benefits. With few other distractions, he was able to channel his energy into work, at least while he was in reasonable health. There was no drinking in cafés or fortnightly visits to the brothel. Meals were served to the residents, so he had few domestic worries (he was a notoriously bad cook). Confined most of the time to the asylum and its garden, he studied nature with great intensity.

That complete isolation helped him to be in the zone, as Murakami recently described the purpose of his own self-imposed isolation when writing a new book. The truth is that for many creators, a space where they can be alone with their thoughts is ideal. Writers and artists regularly go on “retreats,” which is essentially voluntary self-isolation to get work done without the distractions of everyday life.

“Given that creative solutions are by definition unusual, infrequent, and potentially controversial, they are stimulated by the desire to stand out and to assert one’s uniqueness,” writes Sharon H. Kim, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University. “The experience of rejection may trigger a psychological process that stimulates, rather than stifles, performance on creative tasks.”

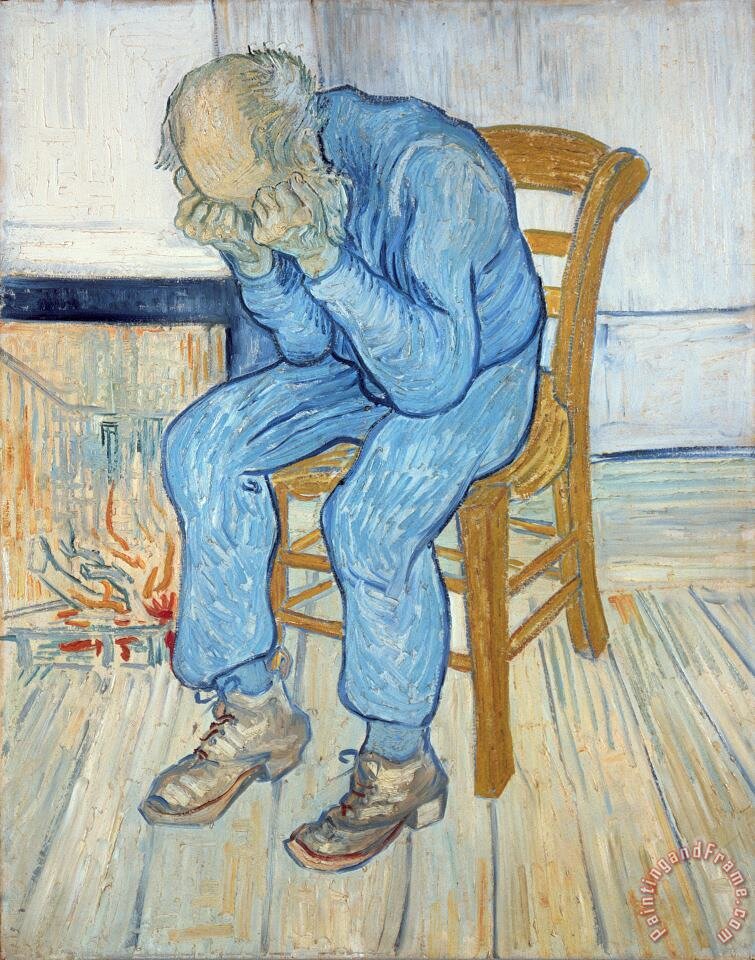

However, its also true that Van Gogh suffered often with bouts of depression and gloom during this phase. In 1888, Van Gogh sent a letter to his brother Theo explaining “I am unable to describe exactly what is the matter with me. Now and then there are horrible fits of anxiety, apparently without cause, or otherwise a feeling of emptiness and fatigue in the head… at times I have attacks of melancholy and of atrocious remorse.” And inching towards the pinnacle of insanity, July 27, 1890, a 37-year-old van Gogh shot himself in the chest with a revolver. So should we consider isolation a boon or a bane for human peace.

The secret potion, it appears, lies in striking a balance. The gap between “solitude” that leads to meta-cognition and creative focus, and “lonliness” is razor-thin. Loneliness and depression (Hemingway called depression “the artist’s reward”) are central to why so many great artists from Hemingway to Plath to Hunter S. Thompson have taken their own life. Sartre sums it up incredibly well by saying, “If you’re lonely when you’re alone, you’re in bad company,” bringing out the idea of being willfully and happily in isolation, when one is happy with oneself and engrossed in creativity. The secret lies in not slipping away to the phase of loneliness and insanity.